our why

Ensuring thriving income for smallholder women farmers

In Central America and Mexico, machismo, in large part, shapes gender norms. At the societal level, machismo grants men more access to political and economic roles, while women are expected to remain confined to domestic duties. Within the household, the heads of the household are generally men, a position which gives men dominance within their families as well. According to the Costa Rica Coffee Institute (ICAFE), values associated with machismo also pervade the coffee sector, values which have led to a widespread belief that the coffee sector is a masculine domain, resulting in the disempowerment of women involved in coffee production. In fact, women coffee producers interviewed by ICAFE stated that the biggest challenge they face is overcoming the misconception of differences between men and women and confronting machismo. However, to understand how women face disempowerment in the coffee industry, it’s important to first understand what power means and what the components of empowerment are.

As a side note, this article will focus almost entirely on gender inequality within the coffee sector, but we recognize that women of different sexual, racial, and ethnic identities, as well as abilities and ages, will experience these inequalities to varying degrees. Unfortunately, at the moment, there is little research on how gender inequalities affect women coffee producers of various backgrounds differently. However, we have tried to include whatever information we could find regarding the intersectional nature of gender inequality.

Defining Power and the Process of Empowerment

Power is “the ability to make choices,” according to Naila Kabeer, a professor of gender and development at the London School of Economics. Empowerment refers to the process of gaining power, and depends on three factors: resources, agency, and achievement.

Resources are the materials, social positions, or services a person has access to and, according to the World Bank, fall into one of four categories: political (i.e. leadership and representation), economic (i.e. land), social (i.e. education and childcare), and time.

The second factor, agency, refers to the ability to make and follow through on choices; for agency to be considered empowering, exercising it must challenge oppressive practices and reflect a strong sense of self-worth.

Combined, resources and agency determine the scope of a person’s potential, or in other words, the range of possibilities of what a person can achieve. Achievement, the third factor in Kabeer’s empowerment framework, refers to the degree to which a person realizes their potential.

All of these factors form the process of empowerment. A person uses their agency to act on resources available to them; the effect of acting on those resources can lead to achievements, or outcomes, which should ideally leave the person with more power than they began with.

Three Areas of Impact:

Lesser Access to Coffee Sector-specific Resources

Some resources in the coffee sector include land, income, education, and credit. Combined with the World Bank’s resource categorization mentioned above, time, labor, and coffee organizations, as well as the leadership positions available in those organizations, can also be considered resources in the coffee sector. Below, we expand on how, for the most part, women coffee producers in Central America and Mexico have reduced access to these key resources.

Land

“families prefer to pass down land to male family members, so oftentimes, only men gain land through inheritance; if women do inherit land, their parcels tend to be smaller and lower quality than the parcels given to men.”

Lesser access to land among coffee-producing women can be partly attributed to machismo. Throughout Latin America, families prefer to pass down land to male family members, so oftentimes, only men gain land through inheritance; if women do inherit land, their parcels tend to be smaller and lower quality than the parcels given to men. Widows who gain land ownership after their husband’s death often either sell the land to quickly gain income or pass the land onto their children.

Although up-to-date statistics about gender disparities in land ownership in the Central American and Mexican coffee industries remain limited, some older studies share key insight about these disparities. A 2010 study noted that 35 percent of land-owning Central American and Mexican coffee producers are women. Yet, the women who participated in this study were members of fair-trade coffee organizations, and women involved in these organizations are generally more empowered than women who are not; overall women’s land ownership in Central America and Mexico is likely lower than 35 percent. In fact, in Costa Rica, although there is no specific statistic, a 2017 study noted that land-ownership is still dominated by men.

In 2018, the International Labor Organization (ILO) conducted a case study on women coffee producers in Mexico, a majority of whom work on smallholder farms. Only about 39 percent of women in the study have either shared or sole land ownership; as for sole ownership in specific, that percentage drops to 21 percent. Interestingly, the ILO noted that land ownership among women coffee producers is higher than Mexico’s national average level of women land ownership, which is about 25 percent, meaning that land ownership in Mexico’s coffee sector is more gender equal than other sectors.

In Central America, some researchers have also noted an increasing trend in migration of men to cities in search of better economic opportunities, leading to what some call the “feminization” of agriculture. Within the coffee sector, the outmigration of men leaves women in charge of managing household coffee production. The word “feminization” suggests that these women are more empowered, but with regard to land ownership, this is not the case; the male family member’s departure, generally, does not lead to a transfer in land ownership to women.

“Time poverty can have a dire effect on quality of life since it limits women’s time to rest, and can lead to worsened health, lower overall wellbeing, and reduced productivity. ”

Time

Women coffee producers often face what researchers call the “double burden,” which requires women to dedicate time to both productive labor, such as their role in coffee production, and reproductive labor, which refers to domestic duties like childcare. Some women face a “triple burden,” meaning they have to balance productive and reproductive labor with organizational labor, which refers to women’s participation in community-based organizations. A double or triple burden can lead women coffee producers to experience time poverty, a situation wherein someone may have too many tasks and not enough time to complete those tasks. For reference, during peak harvest season in Nicaragua, women coffee producers’ workdays can begin as early as 3 a.m. and last until 11 p.m. Time poverty can have a dire effect on quality of life since it limits women’s time to rest, and can lead to worsened health, lower overall wellbeing, and reduced productivity.

Labor

There is little data regarding women coffee producers’ access to labor. However, both the ILO, in the Mexico-based study, and Root Capital, in a Guatemala-based study, noticed that women heads of household generally have smaller family sizes, and therefore less labor available for coffee production. The ILO report also mentioned that family members in women-headed households may have to work more hours per day, so they can’t dedicate as much labor power to coffee production-related tasks.

Income

Root Capital reported that women who participated in their Guatemala study earned lower incomes than men because many of them don’t own land. In relation to the point about outmigration of men to urban areas, one study based in Costa Rica discovered that even if men aren’t physically present in the household, they still exhibit some, though less, control over household income.

“Women family members also aren’t justly compensated for their labor, meaning they earn fewer benefits, like cash, relative to the amount of work they do.”

Root Capital also found that male-headed households in Guatemala, on average, earned higher incomes and revenues from coffee production than female-headed households. This is in part because female-headed households generally have smaller plot sizes and less family members to work the land. Women family members also aren’t justly compensated for their labor, meaning they earn fewer benefits, like cash, relative to the amount of work they do.

In the coffee sector, it’s also difficult for workers to access social security. In the ILO study on women farmers in Mexico, 56 percent of participants stated that they didn’t have access to social security, while the remaining 44 percent of women indicated that they do. The report reinforces the idea that the coffee sector is not a reliable industry to gain social security benefits, and suggests that women coffee producers who have access to social security likely participate in income-generating activities outside of coffee production. Yet, time poverty can prevent women from taking advantage of income-generating opportunities outside of coffee production, so participating in such opportunities is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

Education

In Central America and Mexico, some reports highlight that women involved in coffee production often have lower educational levels than men, findings which indicate that women likely have lesser access to educational opportunities. Although this statistic is a bit outdated, a 2008 study reported that 83 percent of women coffee producers or workers in Mexico either did not finish primary school or received no schooling at all. More current data shows that lower educational levels among women producers still persists. For example, ICAFE’s gender policy, which was released in 2022, confirmed that rural women tend to have lower education levels than women who live in urban areas. Root Capital’s 2014 report stated that women coffee producers in Guatemala have lower literacy rates than men and indigenous women coffee producers were less likely to know Spanish than their male counterparts.

On a more hopeful note, ICAFE discovered that younger women involved in coffee production in Costa Rica, specifically women under the age of 35, have higher educational levels than older women. This information indicates a generational advancement in education levels among women coffee producers, meaning that access to educational opportunities among coffee producers has become more gender equal over time.

Credit

“The issue of accessing credit highlights the interdependent nature of access to resources; oftentimes, women must show they have other resources to gain credit.”

The issue of accessing credit highlights the interdependent nature of access to resources; oftentimes, women must show they have other resources to gain credit. ICAFE also reported that lower educational levels among women producers in Costa Rica hinders their access to financial resources in general. With regard to credit in specific, some women stated that they don’t qualify for credit, and two reasons mentioned were a lack of land ownership and a lack of fixed income.

Coffee Cooperatives and Leadership Positions

Like credit, access to coffee cooperatives is dependent on women’s access to other resources. Some cooperatives, though not all, may require participants to be land owners, and, as explained above, women often aren’t. A double, or triple, burden can reduce the amount of time women have available to successfully participate in and take advantage of membership benefits in cooperatives, let alone gain leadership positions.

With regard to leadership positions, smallholder women only hold about 10 percent of leadership positions in local cooperatives in Costa Rica. At the organizational level, one study showed that all-women cooperatives can face more difficulty in accessing resources compared to mixed-gender cooperatives.

Reduced Agency among Coffee-Producing Women

One of the main measurements of agency is decision-making ability. According to the ICO, the following can also be considered expressions of agency: the ability to move freely, resource control, freedom from risks related to violence, and the ability to express one’s voice to influence policy. Many of these expressions of agency are interrelated, so we will explore how they arise together.

Resource Control and Decision-Making

Since coffee production is viewed as a masculine domain, machismo values influence women’s role in coffee production. In some instances, when landowning women get married, they will oftentimes informally hand over the land to their husbands, leaving them with less control over the land. Even if women own land on paper, many don’t actually control earned income.

With regard to decision-making on financial assets, even though some families interviewed in Nestlé’s Fraijanes, Guatemala study said they divide financial management between men and women, a majority of study participants, 60 percent, believe that men should be the main financial managers. Men and women also have different perceptions on who makes decisions regarding major expenses. In the same study, more men than women think that major expenses are decided by men and women together, while more women than men believe that major expenses are solely decided by men. ICAFE also noted that women often don’t have the autonomy or decision-making power to request loans.

Machismo tends to limit women to less visible roles within coffee production; ICAFE noted that because men are often considered the main decision-makers, women are forced to take on supportive roles, such as roles in administrative tasks. In the study based in Fraijanes, Guatemala, participants indicated that women are solely involved in coffee harvesting. A study done in both Guatemala and Mexico expands on the labor-intensive nature of harvesting tasks, including responsibilities like picking, drying, and washing cherries, as well as quality control. Women who participate in informal wage work and unpaid family work, both of which include productive reproductive labor, aren’t adequately compensated and don’t receive additional benefits like social security; their work is simply seen as “help.”

Since women are expected to allocate more time to household tasks than men, gender norms that arise from machismo can pressure women into prioritizing reproductive labor, like childcare and cooking. These traditional expectations can lead to women face time poverty and bear the double, or triple, burden, all of which can force them to forgo opportunities to participate in decision-making activities outside of the household.

One study noted that women can internalize gender stereotypes regarding coffee production tasks. For example, although some women outright rejected the notion that women are physically too weak to carry out certain tasks compared to men, other women believed so, even though later statements they made contradicted these beliefs.

Ability to Move Freely + Express One’s Voice & Freedom from Violence-related Risks

“Women who want to join all-women cooperatives can experience more pushback from male family members, as noted by some women who joined ASOMOBI, an all-women coffee cooperative based in Costa Rica.”

Women who want to join all-women cooperatives can experience more pushback from male family members, as noted by some women who joined ASOMOBI, an all-women coffee cooperative based in Costa Rica. In fact, on average, Root Capital noted that women cooperative members attend fewer meetings than men. Even if women producers join cooperatives, Root Capital discovered that more women than men stated that they feel some level of discomfort speaking up in large group discussions or participating in decision-making activities. An inability to move freely to access organizations can have serious implications for women’s safety and wellbeing. In general, rural women are more likely to face domestic violence compared to urban women, but are less likely to receive help since rural women have less access to support groups.

Lowered Potential for Achievements

Achievements depend on resources and agency; since machismo reduces access to resources and limits women’s agency, for the most part, women have less potential to realize their goals and empower themselves compared to men.

“there are many barriers to accessing cooperatives and few opportunities to obtain leadership positions, an important resource that requires decision-making”

The most evident area where women experience a lowered potential for achievement is within cooperatives. As noted above, there are many barriers to accessing cooperatives and few opportunities to obtain leadership positions, an important resource that requires decision-making; therefore, oftentimes, women simply don’t have a wide range of possibilities that allow them to enact empowering changes, meaning they have a lower potential to achieve their goals. For example, CoopeAgri, a mixed-gender coffee cooperative in Costa Rica, established an all-women’s committee, and women who were part of this committee felt that they benefited from it, indicating that having access to decision-making positions is likely empowering.

However, as of 2017, CoopeAgri was the only coffee cooperative in Costa Rica that had an all-women’s committee. Root Capital also noticed that, as of 2014, in Guatemala, women are “virtually absent from cooperative boards.” These studies indicate that there exist few leadership positions that allow women coffee producers to use their decision-making skills to achieve outcomes, like policy creation, that will guarantee empowerment.

Why You Should Care:

Eradicating gender gaps, across the board, is beneficial to the coffee industry since it can increase coffee yield and improve quality. With regard to coffee quality, one study reported increased coffee cupping scores when both women and men participated in technical training sessions.

“empowerment within the coffee sector can extend beyond coffee production”

At the societal level, empowering rural women can lead to social, economic, and environmental improvements within rural communities. Humanitarian crises also tend to impact women more severely than men. So, when addressing coffee industry-specific issues and crises, it’s imperative to always consider their impacts on women and ensure that solutions are gender equitable. In the next three articles in this series, we will focus on the following issues that coffee producers face: climate change, income insecurity, and food insecurity, all of which are issues that Bean Voyage has been dedicated towards eradicating within the context of gender inequality.

Although gender inequality is a pervasive issue throughout Latin America and the world, it’s important to keep in mind that individual women experience gender inequalities at a deeply personal level. Furthermore, empowerment within the coffee sector can extend beyond coffee production. For example, the development of greater confidence or an improved sense of self-worth from participating in cooperatives are valuable outside of these organizations. Given these realities, one of the most important reasons to eradicate gender inequalities within the coffee sector is to improve the overall quality of individual women’s lives.

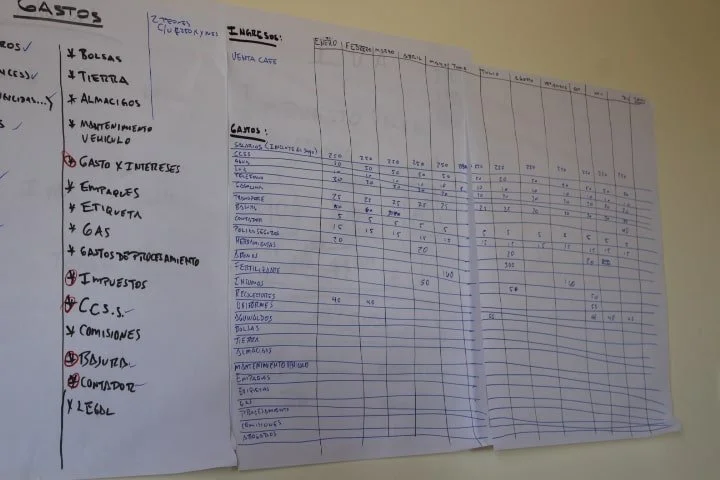

Bean Voyage’s Solution: care trade model

In an effort to break the cycle of poverty affecting coffee-farming communities and support women farmers in leading a thriving livelihood, Bean Voyage works to increase their access to educational opportunities, markets, political engagement, and health and well-being support.

We achieve our mission through the Care Trade model: A bundle of services aiming to increase farm income by facilitating access to knowledge, financing, markets and mentorship for smallholder women coffee farmers.